Monday, February 24, 2020

End Of Campaign: Dark Heresy

Sunday, February 23, 2020

Download Diablo III Eternal Collection For SWITCH

Download Diablo III Eternal Collection For SWITCH

DOWNLOAD

Download-Part-8

GAME SIZE: 14 GB

Friday, February 21, 2020

Q&A With Frictional Writer Ian Thomas

In this blog we've compiled the best questions and answers into an easily readable form. So go get a beverage of your choice and dive into the everyday life at Frictional, narrative game design and tips on networking in the industry! Or, if you're not the reading type, you can also watch the whole video on Twitch.

Have some other questions? Hit us up on Twitter and we will try to answer the best we can!

(Picture commentary from your favourite community manager/editor of this blog, Kira.)

Q: Does the Frictional team scare each other at the office?

We didn't have an office until recently, and even now most people are still remote, so not really!

The thing about being behind the scenes in horror is that it's very difficult to scare yourself, and each other, because you know what's going on. We do play each others' levels every other week, and it's always brilliant to get a decent scare out of a coworker.

Otherwise we don't hide in the office cupboards or anything like that… regularly.

Q: Is it true that developers don't actually play their games?

No - we play our games thousands of times, and most developers do!

It does depend on where you sit in the development chain. If you work for a very big company and only do something like facial models, you might rarely play the game until it's close to completion. But in a team the size of Frictional everyone plays the game all the time. That's how we get our primary feedback and develop our levels before the game goes anywhere near alpha testers.

Q: How about after they're released?

Probably not that often. For me personally there are two reasons, which both have to do with time. Firstly, I'm probably already working on a new thing. Secondly, during the short downtime after a release I'm trying to catch up on games I had to put aside during development. But it depends: for example, when I worked on LEGO games I would later play them with friends, because they're so much fun to sit down and co-op play.

For a couple of years after the release you might be fed up with your game and not want to see it, but then you might come back to it fresh. With SOMA I sometimes tune into livestreams, especially if I'm feeling down. That's one of the kicks you get out of this stuff – knowing which parts of the game people are going to react to, and getting to watch those reactions! That's the best payoff.

Q: Did the existential dread of SOMA ever get to the team?

It's a little different for the dev team, as the horror is a slow burn of months and months, whereas for the players it comes in a short burst. The philosophical questions affected people in different ways, but I don't think we broke anyone. As far as I know we're all fine, but given that a lot of us work remotely, it could well be that one of us is deep in Northern Sweden inscribing magical circles in his front room and we just don't know...

Q: Why did SOMA get a Safe Mode?

SOMA was originally released with monsters that could kill you, and that put off some people that were attracted to the themes, the sci-fi and the philosophy, because they saw the game as too scary or too difficult. Thomas and Jens had discussed a possible safe mode early on, but weren't sure it would work. However, after the game came out, someone in the community released the Wuss Mod that removed the monsters, and that and the general interest in the themes of the game made us rethink. So now we've released the official Safe Mode, where the monsters still attack you, but only if you provoke them – and even then they won't kill you.

|

| You can now avoid one of these three death screens! |

The concept of death in games is a strange one. All it really means is that you go back to a checkpoint, or reload, and all the tension that's built up goes away. The fact is that game death is pretty dull. It becomes much more interesting when it's a part of a mechanic or of the story. We at Frictional have talked about it internally for a while, but it's something we've never really gotten a satisfactory answer to.

So, all in all, even if you turn on Safe Mode, it's not that much different from playing the game normally.

Q: What type of pizza does Simon have in his fridge?

Meat lovers', definitely.

|

| Schrödinger's pizza! And a Mexicana. Unless they mixed it up at the factory. In which case it's also a Schrödinger's pizza. |

Q: What was the funniest or hardest bug to fix in SOMA?

There were so many! You can find some of the stuff in the supersecret.rar file that comes with the installation.

I spent a lot of time fixing David Munshi. His animation really didn't behave and he kept leaping around the place. He was so problematic, especially in this sequence where he was supposed to sit down in a chair and type away at the keyboard. We had so much trouble with that - what if the player had moved the chair? We couldn't lock it in place, because we want the player to be able to mess with these things. We went around trying to come up with an answer for ages.

And then someone on the team went: "Standing desk!". Problem solved! It's silly little things like this which tie up your time.

|

| For all you thirsty Munshi lovers out there. You know who you are. |

Another similar element was the Omnitool. It was a fairly major design thing that we came up with to connect the game characters, and to gate scenarios. We were struggling trying to tie these things together, and then it was just one of those days when someone came up with one single idea that solved so many problems. It was a massive design triumph – even if we realised later that the name was a bit Mass Effect!

Q: Why does using items and elements in Frictional's games mimic real movements?

This is one of Thomas's core design principles: making actions like opening doors and turning cranks feel like physical actions. It binds you more closely into the game and the character, on an unconscious level. We've spent an awful lot of time thinking about ways to collapse the player and the character into one and make the player feel like a part of the world. It's a subtle way of feedback that you don't really think about, but it makes you feel like you're "there".

There's an interesting difference between horror games and horror films in this sense. You would think that horror movies are scarier because you're dragged into the action that moves on rails and there's nothing you can do about it. But for me that kind of horror is actually less scary than the kind in games, where you have to be the person to push the stick forward.

We try to implement this feedback loop in other elements of the game too, like the sound design. When a character is scared it makes their heartbeat go up, which makes the player scared, which makes their heartbeat go up in turn, and so on.

Q: Why didn't SOMA reuse enemies?

It obviously would have been much cheaper to reuse the monsters. But in SOMA it was a clear design point, since each of the enemies in SOMA was trying to advance the plot, get across a particular point in the story, or raise a philosophical question. Thus, the enemies were appropriate to a particular space or a piece of plot and it didn't make sense to reuse them.

Q: Did SOMA start with a finished story, or did it change during development?

The story changed massively over the years. I came on to the game a couple of years into development, and at that time there were lots of fixed points and a general path, but still a lot changed around that. As the game developed, things got cut, they got reorganized, locations changed purpose, and some things just didn't work out.

Building a narrative game is an ever-changing process. With something like a platformer you can build one level, test the mechanics, then build a hundred more similar levels iterating on and expanding those core mechanics. Whereas in a game like this you might build one level in isolation, but that means you don't know what the character is feeling based on what they've previously experienced.

You don't really know if the story is going to work until you put several chapters together. That's why it's also very difficult to test until most of it is in place. Then it might suddenly not work, so you have to change, drop and add things. There's quite a lot of reworking in narrative games, just to make sure you get the feel right and that the story makes sense. You've probably heard the term "kill your darlings" – and that's exactly what we had to do.

A lot of the things were taken out before they were anywhere near complete – they were works in progress that were never polished. Thus these elements are not really "cut content", just rough concepts.

Q: The term "cut content" comes from film, and building a game is closer to architecture or sculpting. Would there be a better name for it?

A pile of leftover bricks in the corner!

Q: How do you construct narrative horror?

Thomas is constantly writing about how the player isn't playing the actual game, but a mental model they have constructed in their head. A lot of our work goes into trying to create that model in their head and not to break it.

A central idea in our storytelling is that there's more going on than the player is seeing. As a writer you need to leave gaps and leave out pieces, and let the player make their own mind up about what connects it all together.

|

| You'll meet a tall, dark stranger... |

From a horror point of view there's danger in over-specifying. Firstly having too many details makes the story too difficult to maintain. And secondly it makes the game lose a lot of its mystery. The more you show things like your monsters, the less scary they become. A classic example of this is the difference between Alien and Aliens. In Alien you just see flashes of the creatures and it freaks you out. In Aliens you see more of them, and it becomes less about fear and more about shooting.

It's best to sketch things out and leave it up to the player's imagination to fill in the blanks – because the player's imagination is the best graphics card we have!

There are a lot of references that the superfans have been able to put together. But there are one or two questions that even we as a team don't necessarily know the answers to.

Q: How do you keep track of all the story elements?

During the production of SOMA there was an awful lot of timeline stuff going on. Here we have to thank our Mikael Hedberg, Mike, who was the main writer. He was the one to make sure that all of the pieces of content were held together and consistent across the game. A lot of the things got rewritten because major historical timelines changed too, but Mike kept it together.

During the development we had this weird narrative element we call the double apocalypse. At one point in writing most of the Earth was dead already because of a nuclear war, and then an asteroid hit and destroyed what was left. We went back and forth on that and it became clear that a double apocalypse would be way over the top and coincidental. So we edited the script to what it is now, but this has resulted in the internal term 'that sounds like a double apocalypse', which is when our scripts have become just a bit too unbelievable or coincidental.

Q: How do you convey backstories, lore, and world-building?

Obviously there are clichés like audio logs and walls of text, but there is a trend to do something different with them, or explaining the universe in a different way. But the fundamental problem is relaying a bunch of information to the player, and the further the world is from your everyday 21st century setting, the more you have to explain and the harder it is. So it's understandable that a lot of games do it in the obvious way. The best way I've seen exposition done is by working it into the environment and art, making it part of the world so that the player can discover it rather than shoving it into the player's face.

Q: How do you hook someone who disagrees with the character?

It's hard to get the character to say and feel the same things as what the player is feeling. If you do it wrong it breaks the connection between the player and the character, and makes it far less intense. Ideally, if the player is thinking something, you want the character to be able to echo it. We spend a lot of time taking lines out so the character doesn't say something out of place or contrary to what the player feels.

With philosophical questions there are fixed messages you can make and things you can say about the world, but that will put off a part of the audience. The big thing when setting moral questions or decisions is that you should ask the question instead of giving the answer. If you offer the players a grey area to explore, they might even change their minds about the issue at hand.

|

| To murder or not to murder, that is the question. |

Q: How do you write for people who are not scared of a particular monster or setting?

In my experience the trick is to pack as many different types of fear in the game as you can, and picking the phobias that will affect the most people. If there's only one type of horror, it's not going to catch a wide enough audience. Also, if you only put in, say, snakes, anyone who isn't afraid of snakes is going to find it dull.

|

| We probably peaked in our first game. What's worse than spiders? (Not representative of the company's opinion.) |

Q: What's the main thing you want to get across in games?

The key thing is that the players have something they will remember when they walk away from the game, or when they talk about it with other people. It's different for different games, and as a developer you decide on the effect and how you want to deliver it. In games like Left 4 Dead delivery might be more about the mechanical design. In other games it's a particular story moment or question.

In SOMA the goal was not to just scare the players as they're looking at the screen, it was about the horror that they would think about after they put the mouse or controller down and were laid in bed thinking about what they'd seen. It was about hitting deeper themes. Sure, we wrapped it in horror, but the real horror was, in a way, outside the game.

Q: What does SOMA stand for?

It has many interpretations, but I think the one Thomas and Mike were going for was the Greek word for body. The game is all about the physicality of the body and its interaction with what could be called the spirit, mind, or soul – the embodiment of you.

The funniest coincidence was when we went to GDC to show the game off to journalists before the official announcement. We hadn't realised there is a district in San Francisco called Soma, so we were sitting in a bar called Soma, in the Soma district, about to announce Soma!

As to why it's spelled in all caps – it happened to look better when David designed the logo!

Q: Does this broken glass look like a monster face on purpose?

I'm pretty sure it's not on purpose – it's just because humans are programmed to see faces all over the place, like socket plugs. It's called pareidolia. But it's something you can exploit - you can trick people into thinking they've seen a monster!

|

| This window is out to get you! |

Q: What is the best way to network with the industry people?

Go to industry events, and the bar hangouts afterwards!

It's critical, though, not to treat it as "networking". Let's just call it talking to people, in a room full of people who like the same stuff as you. It's not about throwing your business cards at each other, it's about talking to them and finding common interests. Then maybe a year or two down the line, if you got on, they might remember you and your special skills or interests and contact you. Me being on Will's stream started with us just chatting. And conversations I had in bars five years ago have turned into projects this year.

You have to be good at what you do, but like in most industries, it's really about the people you know. I'm a bit of an introvert myself, so I know it's scary. But once you realise that everybody in the room is probably as scared as you, and that you're all geeks who like the same stuff, it gets easier.

Another good way to make connections is attending game jams. If you haven't taken part in one, go find the nearest one! Go out, help your team, and if you're any good at what you do, people will be working with you soon.

Q: Can you give us some fun facts?

Sure!

- You can blame the "Massive Recoil" DVD in Simon's room on our artist, David. A lot of the things in Simon's apartment are actually real things David has.

- We try to be authentic with our games, but out Finnish sound guy Tapio Liukkonen takes it really far. We have sequences of him diving into a frozen lake with a computer keyboard to get authentic underwater keyboard noises. It's ridiculous.

- Explaining SOMA to the voice actors was challenging – especially to this 65-year-old British thespian, clearly a theatre guy. Watching Mike explain the story to him made me think that the whole situation was silly and the guy wasn't getting the story at all. And then he went into the studio and completely nailed the role.

- There's a lot of game development in Scandinavia, particularly in Sweden and Norway, because it's dark and cold all the time so people just stay indoors and make games. Just kidding… or am I?

Thursday, February 20, 2020

What I've Learned From Programming Languages

Logo

Logo was my first programming language. Of all of the introductory programming concepts it taught me, the main thing I learned from Logo was how to give the computer instructions in order to accomplish a goal. What exactly did I need to type in to get that turtle to move the way I wanted it to? I had to be precise and not make any mistakes because the computer could only do exactly what it was told. When things went awry, I had no one or nothing to blame but myself.

QBasic

My programming journey really started with QBasic. As with Logo, I learned a ton of things from it because it was one of the first languages I learned, but since I'm going to pick only one thing, I'm going with fun. QBasic showed me that programming could be fun, and that I loved solving coding puzzles and writing basic arcade games in it. For me, QBasic was the gateway to the entire programming world and it was where the fun all began.

Pascal

Pascal was the first language I learned through study and coursework in high school. Of all the things I learned with Pascal, the one thing that stands out most in my memory is functions. Learning how variables and control structures worked came easily to me, but function declarations, definitions, and calls were the first programming abstraction that really stretched my mind. The fact that the argument names in the function call could be different than the parameter names in the function definition, as well as the rules surrounding function scoping all took time to full assimilate. It would not be the last time a programming concept would challenge my understanding, and every time it does, it inspires me to learn even more about programming.

C

The primary abstraction I learned in C was pointers, and with that comes memory allocation. Pointers are an extremely powerful, confusing, and dangerous tool. With them, you can write elegant, concise algorithms for all kinds of problems, and you'll come back to the code later and have no idea how it works. Most languages try to temper and wrap pointers in soft packaging so they can be used more easily and cause less damage. C leaves them raw and exposed so you can use them to their full potential, but you have to be careful to use them wisely or spend hours debugging segmentation faults (or worse).

C++

The first object-oriented language I learned was C++, so of course, the one thing I learned about was classes (and objects and methods and inheritance and polymorphism and encapsulation. This all counts as one thing, right? I won't even mention all of the other new things I learned in C++.) Object-oriented programming was a huge paradigm shift, and not just for me, but for all programmers. That shift came for me with C++, and it was an entirely new way to organize and structure programs. With OOP, programs could support more complexity with less code so we could all write bigger, buggier software. Yay!

Java

I'm trying to keep this list in roughly the order I learned languages, so Java is next. Java finally did away with manual memory management with the introduction of a garbage collector. I actually had to learn to not worry so much about memory, and that took some time after all the scars left by C and C++. Having the language and runtime handle memory allocation and deallocation was liberating and more than a little disconcerting. At the time computers were just getting enough memory to make this form of memory management possible, but now we don't even think twice about using garbage collected languages for most things. Ah, the luxury of 16GB of RAM.

MIPS Assembly

I was in college going down the technology stack while studying computer architecture, so I learned how to program in assembly language with MIPS. MIPS taught me many things, but let's focus on register allocation. All of those variables, arguments, parameters, addresses and constants have to be managed somewhere in the processor, and that place is the register file. Depending on the processor, you may have anywhere from 8 to 32 (or more) named registers to work with, and much of assembly programming is figuring out how to efficiently get all of the program values you need in and out of that register file to use it most efficiently. Programming in assembly dramatically increased my appreciation for compilers.

Verilog HDL

Even further down the technology stack from assembly language is the physical digital gates of the processor, made up of transistors. It turns out that there are a couple programming languages that describe them, and they are aptly named hardware description languages. Verilog is the one I learned first (VHDL is largely the same, just three times more verbose), and it taught me about fine-grained, massively parallel programming. It's the ultimate concurrent programming language because everything, and I mean everything, in a Verilog program happens at once. Every bit of every variable moves through its combinational logic at the same time. The only way to manage this colossal network of signals is with a clock and flip-flops to create a state of the machine that changes over synchronized time periods. It's an entirely different way to program, and it's programming how you want the hardware of a digital circuit to behave.

SKILL

SKILL was the first scripting language I learned, and it was a proprietary language embedded in the super-expensive semiconductor design software called Cadence. Little did I know at the time, but SKILL is also a Lisp dialect. I did not learn much about functional programming with SKILL because it allowed parentheses to be used like this: append(list1 list2) and statements could be delimited with semicolons. However, it still had car, cdr, and cons, and there were still plenty of parentheses. What I learned without realizing it was how to program using lists as the main data (and code) abstraction. It was a powerful way to extend the functionality of Cadence, and to program in general.

MATLAB

My first mathematical programming was done with MATLAB. The one thing above all else that I learned in MATLAB was how to program with matrices to do linear algebra, statistical analysis, and digital signal processing in code. The abstractions provided for doing this kind of computing were powerful and made solving these kinds of problems easy and elegant. (To be clear, the matrix code was elegant. The rest of it, not so much.)

LabView

Yes, I'm not ashamed to say I learned a graphical programming language. Well, maybe a little ashamed. LabView taught me that for certain kinds of programming problems, laying the program out like a circuit can actually be a reasonably clear and understandable way to solve the problem. These types of problems mostly involve interfacing with a lot of external hardware that generates signals that would make sense to lay out in a schematic. LabView also taught me that you can never get a monitor big enough to effectively program in LabView.

Objective-C

I explored iOS programming for a short time around iOS 4, and the thing that I really loved about Objective-C was the named parameters in functions. While it may seem to make function calls unnecessarily verbose, naming the parameters eliminates a lot of confusion and allows literals to be used much more often without sacrificing readability. It turns out to be a pleasantly descriptive way to write functions, and I found that it made code much more clear and understandable.

Ruby

There is so much to love about Ruby, but I'm limiting myself to one thing so for this exercise I'm going to go with code blocks. Being able to wrap up snippets of code to pass into functions so that it can be called by the function as needed is an incredibly awesome abstraction. Plus code blocks are closures, and that just increases their usefulness. I think code blocks are one of the most elegant and beautiful programming abstractions I've learned, and I still remember the giddy feeling I got the first time I grokked them.

JavaScript

JavaScript is the first prototypical language I learned. Programming with objects, but not classes, was a shocking experience. After spending so much time in OOP land, learning how to create objects from other objects and then change their parameters to suite the needs of the problem can be a powerful programming paradigm. There aren't that many different programming paradigms, so every chance to learn a new one is a valuable experience. It teaches you so much about entirely new ways to solve problems and organize your code.

CoffeeScript

I learned CoffeeScript in tandem with Ruby on Rails, since it's the default language used for coding front-end interfaces. With CoffeeScript, I learned about transpiling—the act of compiling one programming language into another instead of an assembly language. CoffeeScript is neither interpreted nor compiled into an assembly language, but instead it's compiled into JavaScript to run in the browser (or Node.js). Learning that you don't have to live with JavaScript's warts if you would rather transpile from another language was certainly eye opening, and pleasantly so.

Python

List comprehensions are to Python what code blocks are to Ruby. It's amazing how much you can express in a simple one line list comprehension. You can map. You can filter. You can process files. You can do much more than that, too. List comprehensions are an excellent feature, and they make Python programming exciting and fun. They are a scalpel, though, and not a chain saw. The best list comprehensions are neat little cuts in code. If you try to make one big one do everything you need to a list, it's going to get complicated and confusing real fast. List comprehensions are a precision tool that solves many kinds of little problems very well.

C#

When Microsoft designed C#, they tried to put everything in it. Then they kept adding more with each release of the language. Somehow through it all, they managed to make a fairly decent and usable language with some nice features. One of the best features that was new to me is delegates. A delegate is basically a special-purpose list of function pointers. Classes can add one of their functions to the delegate of another class. Then the class that has the delegate can call all of the functions attached to the delegate when certain things happen, like when a button in a UI is clicked, for example. This abstraction turns out to be exactly what's needed to make GUI programming elegant and clean. It not only works for the UI, but for all of the different asynchronous events happening in a GUI program.

Scheme

My first experience with a functional language that I knew was a functional language was with Scheme. Learning how powerful functional programming can be was another eye-opening experience, as learning any new programming paradigm can be. Part of what makes functional programming so expressive is how natural it is to use recursion to solve problems. Recursion is used in Scheme like pointers are used in C. It's the other fundamental programming abstraction.

Io

We have finally gotten to the latest languages I learned in quick succession with the 7 in 7 books. Io is the second prototypical language I've encountered, and while it is much simpler than JavaScript, it seems much more flexible as well. I learned that pretty much the behavior of the entire language is controlled by the functions in certain slots of an object, and these slots can be changed to completely change the behavior of the language, add new syntax, and create custom DSLs on the fly. It's incredibly powerful and, well, scary. The ability to change so much about a language while your program is running is fascinating.

Prolog

So far we have procedural, object-oriented, prototypical, and functional programming paradigms. Prolog introduces another one: logic programming. In logic programming you don't so much write a program to solve a problem as you write facts and rules that describe the problem and have the computer search for the solution. It's an entirely different way to program, and when this paradigm fits the problem well, it feels like magic. The fundamental abstraction that you learn in logic programming is pattern matching, where you write rules that include variables and both sides of each rule need to match up. There is no assignment in the normal sense, though, and one program can generate multiple solutions because multiple combinations of values are attempted for the set of variables. Prolog will definitely change the way you think about programming.

Scala

The one thing to learn with Scala is concurrency done well with actors and messages. Actors can be defined with message loops to receive and process messages, and they can be spawned as separate threads. Then, threads can send messages to these actors to do work concurrently. The actor model of concurrency is a lot safer than many of the models that came before it, and it will help programmers develop much more stable concurrent programs to utilize all of those extra cores we now have available in modern processors.

Erlang

If Scala taught me something about concurrency, Erlang taught me how to take concurrency to the extreme. With Erlang, concurrency is the normal way of doing things, and instead of threads, it uses lightweight processes. These processes are so easy to start up, and the VM is so rock solid, that it's actually easier to let processes fail when they encounter an error and start a new one instead. The mantra with Erlang is actually "Let it crash," which was simply shocking to me. After learning for decades to write careful error-checking code, seeing code with sparse error checking that instead monitored processes and restarted them if they failed was a big change. It's a fascinating concept.

Clojure

One of the Clojure features that stood out to me was lazy evaluation. With the addition of a number of constructs, Clojure is able to delay computation on sequences (a.k.a lists) until the result of the computation is needed. These lazy sequences can significantly improve performance for code that would otherwise compute huge lists of values that may not all be used in subsequent calculations. Generators can also be easily set up that will feed values to a consumer as needed without having to precompute them or specify an end to the sequence of values. It's a great trick to keep in mind for optimizing algorithms.

Haskell

The big take-away with Haskell is, of course, the type system. It's the most precise, well-done type system I've ever seen, yet it's not as onerous as it sounds because it leverages type inference. I was worried when starting out with Haskell that I would constantly be fighting the type system, but that's not at all the case. It still takes some time to design the types of a program properly, but once that's done it provides great structure and support for the rest of the program. I especially learned from this experience to not write off a certain way of programming just because I've gotten burned by it in the past with other languages. One language's weakness can be another language's strength, and a perceived weakness may not be inherent to the feature itself.

Lua

With Lua I learned that if one fundamental abstraction is made powerful enough, you can make the language be whatever you want it to be. Lua's tables provide that abstraction, and depending on how you use them, you can program as if Lua is an OO language, a prototypical language, or a functional language. You can also ignore all of that and use it as a procedural language if you so choose. The tables allow for all of these options and leave the power in the hands of the programmer.

Factor

The final programming paradigm I've learned happened through Factor, and it's stack-based programming, also known as concatenative programming because of the post-fix style of the code. Because of the global stack on which all values are pushed and popped (well, almost all), the stack needs to be constantly kept in mind when analyzing the code. This concept is mind-bending. I'm sure it gets better with practice, but for how long I've used the language, it's a significant mental effort to keep program execution straight. However, some problems can be solved so neatly with stacks that it's definitely worth keeping this paradigm in mind. Stacks can be used in any language!

Elm

Elm taught me another way to do UI development with signals. While C# introduced me to delegates with their PubSub model, signals are a finer-grained, more tightly integrated feature that makes front-end browser development so much cleaner. Signals can be set up to change state, to kick off tasks or other processing, or to chain different actions together when specified events happen. Signals take delegates to the next level, and provide a lot of functionality that you'd have to build yourself with delegates.

Elixir

Elixir combines a lot of things from a lot of other languages, but one thing not covered yet that I learned in Elixir is metaprogramming with macros. Macros are an extremely powerful tool for compacting programs and making difficult or tedious problems much simpler. Any time you're repeating similar code over and over, it's best to start thinking of how to implement it more quickly and efficiently using a macro. Spending any amount of time copy-pasting code and making slight changes is a dead giveaway that a macro could be used instead. Metaprogramming has a way of wringing the drudgery out of programming. It's simply magical.

Julia

The killer feature that I learned in Julia is definitely multiple dispatch. While other languages have to deal with calling the same function with different types in various convoluted ways, Julia says "Screw it. Just give all of those functions the same name with different types, and I'll figure it out." It's a great feature when you need it, and since Julia is built for scientific computing, it probably comes up a lot.

miniKanren

I've learned about how great logic programming can be for certain types of problems, and I've learned how great functional programming can be for other types of problems. Now miniKanren has shown me how powerful it is to combine these two paradigms into one language. Since logic programming works well for isolated logic problems, but doesn't do so well for implementing a complete program, putting it into a functional language bridges that gap so that you can create a fully working program. Having Clojure there to provide the input and process the output of the logic program really ups the ante for what can be accomplished in miniKanren.

Idris

Idris takes the powerful type system of Haskell and turns it up a notch. The novelty of Idris' type system is dependent types that allow types to be specified in relation to other types using characteristics of those other types and operations. It's basically making the type system programmable. Types can be specified so that arrays have a certain length, the output of a function has the same length or combination of lengths of its inputs, or any other set of operations can be done on characteristics of a function's types to specify the dependent type. It is a really powerful type system that stretched my mind even more than Haskell did.

As you can see, I've come in contact with a lot of languages. It looks like 31 so far, if I haven't forgotten any, and I've learned something valuable from each one of them. Some languages have taught me much more than others simply because of where they fell on my programming journey, but old or new, popular or unknown, every language has something to teach. While this is a lot of languages, there are notable omissions including Go, Rust, Swift, and Kotlin, just off the top of my head. I imagine that those languages, too, would have much to teach me about new programming features or improvements to concepts I already know. That's the beauty of learning new programming languages: there's always something more to learn about the craft. You just have to be ready for it.

AP 2006, Infiltrate!

Please donate to my Extra Life campaign!

Sean's Extra Life page

Andrew's Extra Life page

Rick's Extra Life page

Bryce's Extra Life page

Marc's Extra Life page

Infiltrate on Random Terrain

Ed Salvo interview by Scott Stilphen

Infiltrate (Blue) on Atarimania

No Swear Gamer 492 - Infiltrate

Wednesday, February 19, 2020

One Piece: Burning Blood - Gold Edition Free Download

• Featuring Devil Fruits plus Haki can be used to do Massive special Moves and take down the fiercest opponents.

• Burning Blood Game is all about style that will reheat fan's nostalgia and peak the interest of curious new pirates.

• New true-to-series pirate free-for-all Activated at will these unique abilities can increase the player's attack power.

• Perfect Blend Manga x Anime x Game taking advantage of the rich History of One Piece & character expressions.

• Plus strategize how and when to use these New Epic Special Abilities to unleash their Maximum Fighting potential.

♢ Click or choose only one button below to download this game.

♢ View detailed instructions for downloading and installing the game here.

♢ Use 7-Zip to extract RAR, ZIP and ISO files. Install PowerISO to mount DAA files.

(Your PC must at least have the equivalent or higher specs in order to run this game.)

• Processor: Intel Core i3-4170 @ 3.70GHz or faster for better experience

• Memory: at least 4GB System RAM

• Hard Disk Space: 15GB free HDD Space

• Video Card: NVIDIA@ GeForce@ GTX 460 or faster for better gaming experience

If you have any questions or encountered broken links, please do not hesitate to comment below. :D

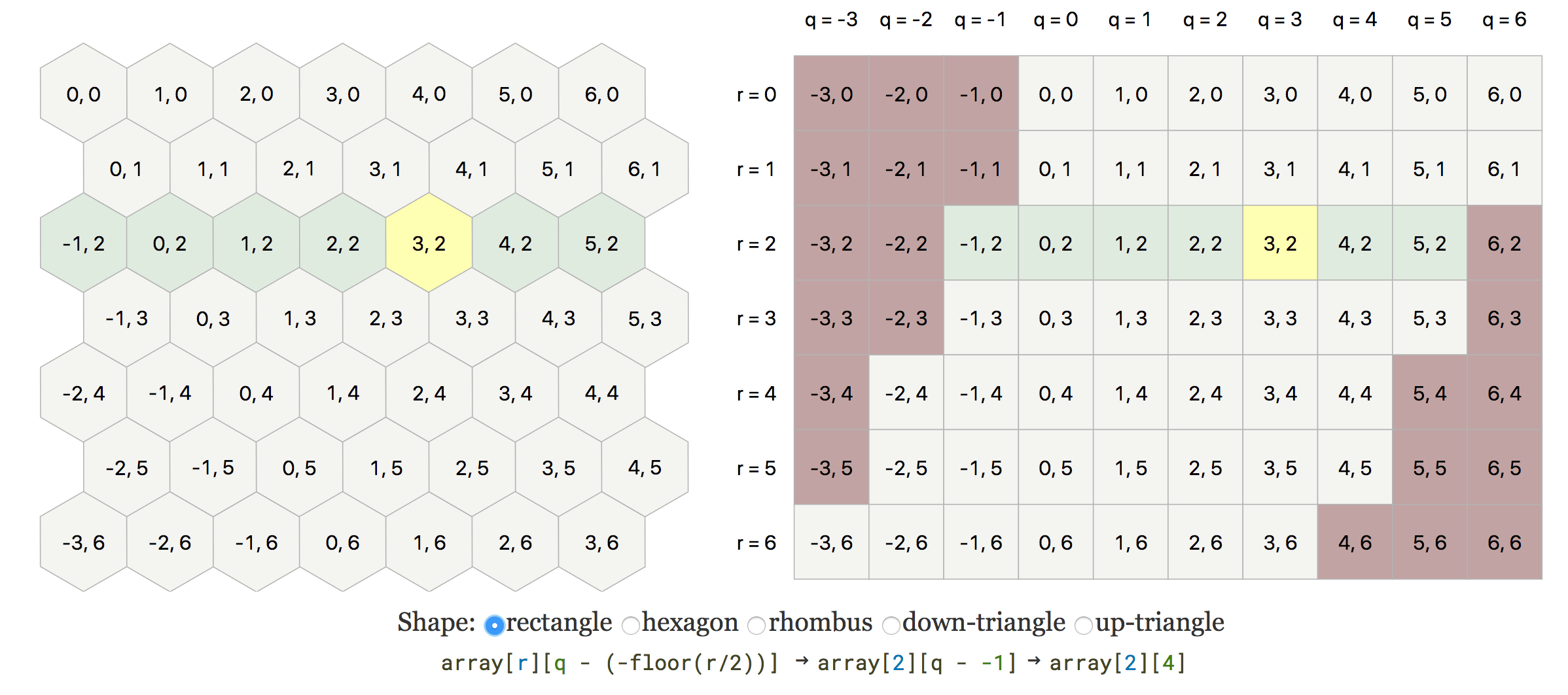

Improving Hexagon Map Storage Diagram

Last week, I decided to improve the map storage section of the hexagon guide. This section had a diagram that suggested the use of a 2D array, but then it presented formulas that didn't look like what was shown. Reader feedback made me realize this section was confusing. I was mixing two separate steps here.

- Store the map in a 2D array.

- Slide the rows to the left to save space.

The diagram showed step 1 but not step 2. The formula under the visualization showed step 2. Mismatch!

I think it's worth having two separate diagrams here. I couldn't figure out where to place the second diagram in the page layout, so I decided to instead make the one diagram animate between the two different approaches.

One of the advantages of writing text over making videos is that I can treat it as a "living document" that improves over time. The improvements are less frequent the longer the document has been around, but I am still updating the pages I wrote in the 1990s, and I intend to continue improving the new ones too.

Thursday, February 13, 2020

Brave Browser the Best privacy-focused Browser of 2020

Out of all the privacy-focused products and apps available on the market, Brave has been voted the best. Other winners of Product Hunt's Golden Kitty awards showed that there was a huge interest in privacy-enhancing products and apps such as chats, maps, and other collaboration tools.

An extremely productive year for Brave

Last year has been a pivotal one for the crypto industry, but few companies managed to see the kind of success Brave did. Almost every day of the year has been packed witch action, as the company managed to officially launch its browser, get its Basic Attention Token out, and onboard hundreds of thousands of verified publishers on its rewards platform.

Luckily, the effort Brave has been putting into its product hasn't gone unnoticed.

The company's revolutionary browser has been voted the best privacy-focused product of 2019, for which it received a Golden Kitty award. The awards, hosted by Product Hunt, were given to the most popular products across 23 different product categories.

Ryan Hoover, the founder of Product Hunt said:

"Our annual Golden Kitty awards celebrate all the great products that makers have launched throughout the year"

Brave's win is important for the company—with this year seeing the most user votes ever, it's a clear indicator of the browser's rapidly rising popularity.

Privacy and blockchain are the strongest forces in tech right now

If reaching 10 million monthly active users in December was Brave's crown achievement, then the Product Hunt award was the cherry on top.

The recognition Brave got from Product Hunt users shows that a market for privacy-focused apps is thriving. All of the apps and products that got a Golden Kitty award from Product Hunt users focused heavily on data protection. Everything from automatic investment apps and remote collaboration tools to smart home products emphasized their privacy.

AI and machine learning rose as another note-worthy trend, but blockchain seemed to be the most dominating force in app development. Blockchain-based messaging apps and maps were hugely popular with Product Hunt users, who seem to value innovation and security.

For those users, Brave is a perfect platform. The company's research and development team has recently debuted its privacy-preserving distributed VPN, which could potentially bring even more security to the user than its already existing Tor extension.

Brave's effort to revolutionize the advertising industry has also been recognized by some of the biggest names in publishing—major publications such as The Washington Post, The Guardian, NDTV, NPR, and Qz have all joined the platform. Some of the highest-ranking websites in the world, including Wikipedia, WikiHow, Vimeo, Internet Archive, and DuckDuckGo, are also among Brave's 390,000 verified publishers.

Earn Basic Attention Token (BAT) with Brave Web Browser

Try Brave Browser

Get $5 in free BAT to donate to the websites of your choice.Followers

Blog Archive

-

▼

2020

(365)

-

▼

February

(9)

- End Of Campaign: Dark Heresy

- Download Diablo III Eternal Collection For SWITCH

- Q&A With Frictional Writer Ian Thomas

- What I've Learned From Programming Languages

- The Green Apartment + DOWNLOAD + TOUR + CC CREATOR...

- AP 2006, Infiltrate!

- One Piece: Burning Blood - Gold Edition Free Download

- Improving Hexagon Map Storage Diagram

- Brave Browser the Best privacy-focused Browser of ...

-

▼

February

(9)